Guidance

The NACUBO Higher Education Economic Models Project was initiated to help ensure that the economic models of colleges and universities in the 21st century provide students the opportunity to enrich their minds, their lives and their communities, as well as enable institutions to pursue their missions in research and service.

To support these goals, we have gathered input from hundreds of leaders and observers of higher education to better understand the changes that are needed to ensure continued financial sustainability and the forces that inhibit that change on college and university campuses. Most recently, we have developed and tested a framework that facilitates structured inquiry and discussion about an institution’s economic model as well as serves as a framework for innovation. This website is the outgrowth of that research.

The Leadership Challenge: No Silver Bullet

As we have talked with higher education leaders, several individuals have asked us for the “silver bullet” to resolving higher education’s sustainability issues. Some, coming from the worlds of accounting and business, believe there must be an algorithm or formula that will resolve their institution’s resource shortfalls. Others believe the enrollment management mantra that “growth through effective marketing” is the solution.

While we concur that enhanced accounting and budgeting strategies can lend insight for more effective resource acquisition and deployment, and that understanding the nuances of student demand can enhance planning for delivery, we do not believe there is any singular answer to institutional sustainability. Rather, institutions must undertake a holistic review of what they do, how they do it and for whom. This requires candor and transparency, willingness to hear conflicting perspectives and courage to make difficult decisions.

Change in any organization is not for the faint of heart, and change within the complex organizational and decision-making structures of higher education is an even greater challenge. However, innovation and transformation are needed to move colleges and universities to financial sustainability. For many institutions, change is not merely necessary, but essential.

To assist colleges and universities in developing their own paths to sustainability, we have created this website to help you along the economic models project journey. This guide does not propose any one solution nor a simple checklist for institutions. Rather, we believe that the unique attributes of colleges and universities in the United States are one of the industry’s strengths.

Each institution must examine for itself its mission, structure, strengths and resources and assure the necessary alignment across these dimensions

Thus, each institution must examine for itself its mission, structure, strengths and resources and assure the necessary alignment across these dimensions. Questions, provided by NACUBO members from across the industry, are intended to facilitate discussion. Not all will apply to every institution, and each college or university will need to judge for itself which domains and questions are most useful in exploring current and future options.

This website is intended for use by college and university leaders—chief business officers, presidents, board members, chief academic officers and others in academe, as well as policymakers who are interested in understanding the operational aspects of higher education’s economic models—to spark and guide critical conversations about their institution’s economic model and the changes necessary to sustain it.

As colleges and universities undertake these self-assessments, institutional leaders will play critical roles in facilitating difficult conversations. We intend that the focus of conversations be on the institutional level. While similar processes might be used to contemplate the future of an academic department or unit, a research center, or even a college within a university, resources found in this guide will center on institutional strategies and futures.

How to begin? One way to start work with this guide is to print out the sets of questions. Beginning with the questions about mission, distribute copies to constituents and ask them to rank the questions as “Critical,” “Important,” or “Irrelevant.” Those ranked “Critical” should be the ones that need to be answered for the institution to move forward. They may be hot button issues that have previously been avoided, or they may reflect aspects of the institution have been taken for granted and, hence, assumed to be unchangeable or immovable. Questions assessed as “Important” should include those whose answers will impact specific directions and may reflect activities already underway. “Irrelevant” include both those that touch on parameters such as religious affiliation that may not apply to the institution, as well as those whose answers will have little bearing on the actions to be taken. Ensuing discussion should focus on sharing of constituent rankings and perspectives to gain consensus on the questions to be explored further within the group and with other stakeholders in the college or university’s future. Next steps will include collecting quantitative and qualitative data to answer the strategic questions. For guidance on how to did, look under the “Using Analytics to Answer EMP Questions: tab.

- Plan Ahead – understand and examine your institution’s economic model whether the college or university is thriving, surviving or diving

- Focus on and create clarity about institutional mission and purpose

- Develop an aligned leadership team with shared vision to guide, coordinate and communicate the process

- Establish trust and engage with constituents; focus on the majority – the champions and supporters – while respecting the resisters

- Share the brutal facts to foster transparency and activate a sense of urgency

- Intentionally support and utilize the elements of institutional culture that encourage thoughtful examination and critique of the institution’s economic framework and development of creative, effective responses

- Focus on strategy and innovation; incentivize bold action and remove barriers, tangible and intangible

- Utilize data and evidence in decision-making

- Look holistically at the institution, planning for the long-term and mitigating unintended consequences

- Celebrate short-term wins as steps toward institutionalizing new processes, programs, structures and behaviors

- Learn from peers – look at others’ successes for inspiration and others’ challenges for learning; share your experiences and solutions for the betterment of the industry

For additional assistance in facilitating campus conversations, search keyword “facilitation” in the EMP Library.

Metrics abound for measuring college and university performance. With few exceptions, there is widespread agreement that metrics are important. They are routinely used to evaluate finances, budget, space utilization, physical plant, academics, development and other functional areas within institutions.

What matters most is that the organization identifies metrics that are meaningful to its situation and that it nurtures a culture that shares and values data and analytics for strategic decision-making.

Historically much of the data was used simply to describe institutional activities: how many students were enrolled? How efficiently were classrooms utilized? What was the return on investment of endowments? Today colleges and universities are engaging with analytics to predict outcomes to better understand the impact of initiatives and to better inform strategy, particularly that related to institutional outcomes and student success.

Institutional sustainability is the outcome focus of the NACUBO Economic Models Project (EMP). Consequently, metrics used to monitor the institution were culled from a range of sources including rating agencies, accounting firm publications, higher education and accreditation organizations, EAB’s Metrics Compendium, NACUBO research and academic studies.

As can be seen from the array of measures cited in those reference, there is no one metric nor even one set of metrics deemed useful by all. The metrics or dashboards that work for one organization may or may not work for another. And, no single institution has the time or resources to monitor all of the suggested metrics.

What matters most is that the organization identifies metrics that are meaningful to its situation and that it nurtures a culture that shares and values data and analytics for strategic decision-making.

While individual institutions should evaluate those that are most pertinent to their decision-making, a survey by NACUBO of Chief Business Officers participating in EMP focus groups and meetings suggests the following metrics are most useful:

- Student to Faculty Ratio

- Facility Utilization Rate

- Net Tuition and Fees Contribution Ratio

- Net Tuition Per Student

- Primary Reserve Ratio

- Tuition Discount Rate

- Debt Service as a Percent of Operating Budget

Decreases in any of the first five or increases in the last two may indicate problems and certainly require investigation, particularly when accompanied by other negative indicators, when benchmarked against peers or when part of a trend. Most of this data focuses on hindsight, yielding descriptive analysis; some will generate further insight as they are used to populate predictive models.

In Inside Higher Ed’s 2018 Survey of College and University Business Officers, over half of the respondents – and 65 percent or more of business officers are private, nonprofit institutions – found the following to be “very important” measures of financial health:

- Net Operating Revenue

- Change in Unrestricted Net Assets

- Rate of Net Tuition Growth

We’ve identified key strategic questions related to our college or university’s economic model, now what?

Institutions of higher education and the people that work in them are known for their ability to ruminate, reflect, and debate issues, sometimes ad nauseum. While the focus on never-ending fact finding in search of the perfect answer can be an effective driver for research programs, unending discussion and the pursuit of unanimous consensus can forestall timely implementation of necessary innovation to the detriment of the college or university’ economic sustainability.

Consequently, after the institution has efficiently completed the first phase of its economic models journey and identified the strategic questions related to its financial sustainability, phase two must promptly commence to answer the questions and initiate actions to implement meaningful change. Not all of the questions will have quantitative or quantifiable answers, and many will require both qualitative and quantitative responses, but analytics will be a necessary tool to evaluate and understand the impact of variables on outcomes and to prove or disprove assumptions and organizational lore. Thus, just as descriptive and predictive data and metrics informed the college’s need to begin the economic models journey, predictive and prescriptive data science will be critical to provide data-informed answers to the strategic questions.

In the following we outline a process for undertaking this next phase, particularly the analytical aspects. As this phase is undertaken, seven principles must be kept in mind:

-

Start with Mission: Which questions will yield the most insight and strategic value?

-

Bridge silos: What do we need to learn or understand about the rest of the institution to provide useful analysis?

-

Identify collaborators: Who on campus needs to partner in the effort to secure, understand and analyze the data and communicate results?

-

Share and simplify: How will we mitigate information system limitations, data hoarding, and data complexity, and integrate disparate data sets?

-

Maintain integrity: How will we address potential implicit or explicit biases and legal requirements that could impact the analysis?

-

Visualize and apply: What actions can we take to reach the future we envision, and what outcomes of those actions are possible?

-

Communicate transparently: How do we make the analysis and results meaningful and actionable for decision-makers?

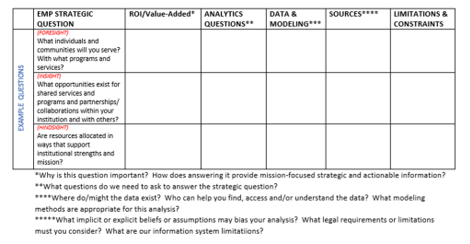

The selected strategic economic model questions may range from understanding in hindsight to gaining insight to developing foresight, corresponding to increasingly complex phases and types of analytics and modeling. In addition, the strategic questions may need to be broken into smaller questions or components in order to identify metrics for analysis. A template such as the following may facilitate this process.

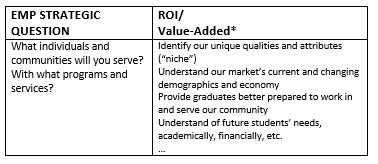

The template suggests first clarifying the purpose for asking the question and the intended outcomes of the inquiry. That is, what is the value added to the institution’s decision-making of asking and answering the question? How will it impact the future direction of the college or university? An example of this for one of the Mission-related strategic questions is shown below; answers will vary for each college or university:

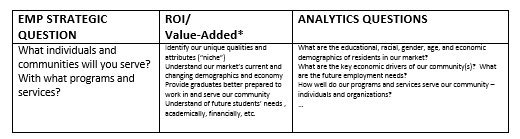

As noted above, strategic questions need to be broken down into more detailed questions. These questions explore specific aspects or nuances of the college’s environment or activities. The following shows possible questions that a college or university might ask to understand the evolving needs of the communities in its market:

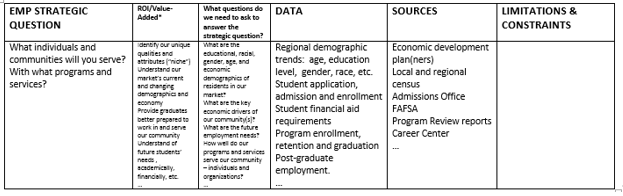

Understanding the context – the purpose and desired outcome – as well as the nuances of the question to be answered, one can then proceed to identify the data needed and methods to be used. If a variety of perspectives have not yet been brought into the discussion, now is the time to seek out potential collaborators among other campus constituencies. Who might these possible partners be? They may include institutional researchers, faculty from data science related disciplines, and others, depending on the nature of the questions. Data requirements and potential sources may also help identify potential partners. For the example above, additional collaborators might include external or community relations staff, workforce development personnel, economists, and academic affairs leadership. Bridging these silos may yield “new” sources of data and analytic tools as well as better understanding of the variables at play and a broader understanding of the impact of potential actions.

As data and its sources are identified, limitations and constraints must be kept in mind. There may be limitations in the data, based on how it is collected, stored or reported, or in non-integrated/isolated institutional information systems. There may be organizational divides between those who know what data exists and how to access it and those who understand how to put it to effective use. There may be constraints in modeling techniques. And there may be legal restrictions on access to or use of information, to assure privacy and security. Fortunately, many of these will be obvious to the analysts. What may not be so apparent, however, are the implicit biases in the data selected and the assumptions made. For example, demographic data may embed historical discriminatory actions and patterns.

Descriptions of analytic methodologies and their appropriate application are beyond the current scope of this site. References on experimental design, statistical analysis, systems dynamics and modeling and other techniques abound, and a few are included in the site Library. Most financial and accounting staff will have encountered some study of these in their undergraduate or graduate business coursework. Institutional Researchers will be an excellent campus resource for more complex analyses as are faculty in mathematics, engineering and other decision-science disciplines.